During the 1930s, there were only two serious giants in the animation field. The first was, of course, Walt Disney Studios. But the other, an outfit that has been sadly neglected today, was Fleischer Studios, run by Max Fleischer and his talented brother Dave.

During the 1930s, there were only two serious giants in the animation field. The first was, of course, Walt Disney Studios. But the other, an outfit that has been sadly neglected today, was Fleischer Studios, run by Max Fleischer and his talented brother Dave.Max was especially fascinated with technological innovation, as well as art. He had worked in the art department of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (even introducing a short-lived comic strip, Little Elmo, in 1904), before becoming the art editor at Popular Science Monthly in 1914. In 1911, he created the rotoscope, an animation innovation that is still used today in one form or another. Rotoscoping allows an animator to film a complex movement with a live action actor, and then animate over that actor, producing (in theory) realistic movement in cartoon form: this is the grandfather of the motion capture techniques used to create Gollum in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings, and the dead-eyed soulless things in Polar Express. Fleischer was granted a patent for the rotoscope in 1917, but found out later that a similar device had already been invented (which is why he didn't sue Disney for using it in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937).

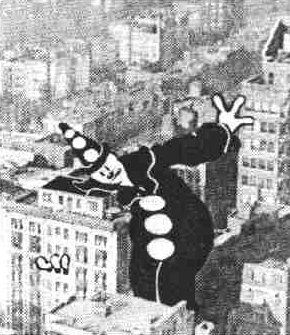

The rotoscope was tested by filming Dave gamboling in a clown suit, and animating a full cartoon over it. The process took nearly a year; when Max tried to sell the film to Pathe in 1916, they were impressed but felt a year was laughable for cartoon production. Max came up with another idea: wrap a live action introduction and ending around the cartoon, with the animated clown capering around on a blank sheet of paper or playing with drawing supplies. By introducing a significant live action element, production time was cut down. Out of the Inkwell was born. John R. Bray saw it, loved it, and offered them a spot in his Paramount-Bray Pictograph film magazine.

Before that, however, there was a war to fight: Max made training films for Bray, while Dave worked in the US Army as a film cutter. They still managed to turn out a few films, such as the lyrical Experiment No. 1 (1918), but it wasn't until after the war that production on an Out of the Inkwell series could begin in earnest. Though the series was meant to be monthly, it could never keep that schedule. However, the series proved popular. From a technical standpoint, the rotoscoping allowed a smoother animation than anyone else's. Dave directed, did story, and acted in the clown suit as one of the earliest recurring cartoon characters, KoKo the Clown. Max, however, was quick to claim credit, and the two brothers would clash fiercely. In 1921, they formed Out of the Inkwell Films, Inc., and were able to hire animators (as well as their younger brother Joe as an electrician and camerman). They not only produced more KoKo cartoons, but worked on educational cartoons, such as The Einstein Theory of Relativity (1923, commended by Albert Einstein himself) and Darwin's Theory of Evolution (1923, which was not shown in the South).

Always attempting to innovate, Max Fleischer soon created the KoKo's Song Car-Tunes series. In this series, KoKo the Clown would step out of the inkwell, change into a conductor's suit, and the lyrics to a song would appear on screen. Then a bouncing ball would jump onto each lyric to prompt the audience to sing along while an organist played the music. It started with Oh Mabel in 1924 and became quite a crowd-pleaser, continuing on until 1927 (and was briefly revived in 1929 as the Screen Songs series). To achieve this, Max created synchronized sound for the films so that the live audience and the bouncing ball would be in synch. Unfortunately, he didn't realize that layering the sound onto the film was a simple matter (he had already figured out the timing), so Disney beat him to sound.

Always attempting to innovate, Max Fleischer soon created the KoKo's Song Car-Tunes series. In this series, KoKo the Clown would step out of the inkwell, change into a conductor's suit, and the lyrics to a song would appear on screen. Then a bouncing ball would jump onto each lyric to prompt the audience to sing along while an organist played the music. It started with Oh Mabel in 1924 and became quite a crowd-pleaser, continuing on until 1927 (and was briefly revived in 1929 as the Screen Songs series). To achieve this, Max created synchronized sound for the films so that the live audience and the bouncing ball would be in synch. Unfortunately, he didn't realize that layering the sound onto the film was a simple matter (he had already figured out the timing), so Disney beat him to sound.Max also invented an important process: the in-between animator. In animation, most animators (think of today's greats like Andreas Deja and Glen Keane) draw only key shots, while an in-betweener comes in and draws the action between the key shots. Max came up with the notion (based on Bray's assembly-line theory), along with animator (and future Disney vet) Dick Huemer. Max also attempted to move into distribution--Margaret J. Winkler had developed a state-to-state system of middle-men which saw royalties arrive too late from individual theaters--and formed Red Seal Pictures in 1924. Unfortunately, Red Seal went bankrupt within two years. Fleischer again tried to distribute his own pictures under a company called The Inkwell Imps, but the independent producer Max had allied himself with, Alfred Weiss, was a crook and went out of business. Max's dream of independence was crushed, and instead he set himself up at Paramount Pictures. Although the company was called Fleischer Studios Inc., the company was a subsidiary of Paramount, who would hold all the copyrights.

Sound devastated the animation field in 1927, and only those who could adapt quickly survived. Max took up sound and ran with it in 1929, creating the Screen Songs series (bouncing ball still firmly in place) with The Sidewalks of New York. Even though the Out of the Inkwell series was still fun--the cartoon KoKo's Earth Control (1927) in which KoKo and his dog Bimbo find a lever that accidentally destroys the planet, is a surreal masterpiece--Max saw sound coming and decided the adventures of KoKo had come to an end. Lest he become a relic like Felix the Cat was about to, Dave made KoKo Needles the Boss (1927) the last Out of the Inkwell cartoon.

Trumpeting the advent of sound, the Fleischers created a new series called Talkartoons, a series which was meant to star KoKo's dog Bimbo for a sense of continuity and audience identification. The first Talkartoon, Noah's Lark, premiered in October 1929. It featured music in much the same way Disney's Silly Symphonies, developed concurrently, did. Another Fleischer brother, Lou, was hired as musical director.

Trumpeting the advent of sound, the Fleischers created a new series called Talkartoons, a series which was meant to star KoKo's dog Bimbo for a sense of continuity and audience identification. The first Talkartoon, Noah's Lark, premiered in October 1929. It featured music in much the same way Disney's Silly Symphonies, developed concurrently, did. Another Fleischer brother, Lou, was hired as musical director.For more information continue on to this website

-angela

Alfred Weiss is like the Gustave Anjou of Cartoons (Explanation, Gustave Anjou is a genealogist and he is responsible for fake genealogies.)

ReplyDelete