__________________________________________________________

John Kricfalusi, Takashi Murakami, and the Divide Between Fine Art and Cartoon Animation

By Lily Hoyda, for History of Animation

I am very adamant in my opinion of animation and the motion picture as fine art. An often long and in-depth process, sequential art in motion, whether possessing a narrative or more abstract, can be incredibly expressive and every bit as worthy of attention and consideration as the traditional fine arts in any museum or gallery. That being said, there is a stark contrast of opinions amongst many that all equally adore the animated arts: those that believe animation is high art, and those that are happy with animation as low art. Are the truest forms of animation present in cartoons intended for children? If so, are we to consider cartoon animation and "fine art" or abstract animation separate pursuits? Is one less meaningful than the other? For this purpose, I look to two prevalent artists and animators of completely different stock: John Kricfalusi, and Takashi Murakami.

John Kricfalusi, or John K., is a Canadian-born cartoonist, and the creator of the popular 1990's cartoon, The Ren & Stimpy Show, as well as the founder of the studio Spümcø. Having worked on various cartoons leading up to that point and earning the favor of the Clampett family (Mighty Mouse, The New Adventures of Beany and Cecil, etc), Kricfalusi had made himself known for two major things: Wanting all the animators to have direct creative influence over the shows, rather than "fat-cat" executives, and pushing the envelope of what the Censors and networks found appropriate for children's programming. A thick skinned, bold risk-taker, he strove to make each show he worked on push the limits of tone and creativity, but ultimately lost in his struggle for more power on his projects, and the shows were ultimately canceled. Now, it would be false and unfair to claim that he didn't make a lot of important changes to the standard thinking in children's television. Ren & Stimpy was a game-changer, raising the bar for all shows to come after it in terms of content, humor and style.

Since the rise and fall of John K.'s empire, he has continued to live on and spread his opinions on modern animation through his blog, as well as his small side projects and scattered commissions. Said blog contains his musings on classic cartoons, movies, storybooks and artists from all walks of life. It's also home to his anti-feminist, anti-"hippie" and anti- P.C. rantings, where he makes claims as to why modern children's animation is so bland and bleak. He often blames popular arts universities, such as California Institute of the Arts, for leading young artists down the path of streamlined, ugly, and cookie-cutter animation jobs at major production companies. He blames "moms" and executives for completely controlling the creative process to the point of sterilizing it so as to strip it of individuality and offensiveness. Such conspiracy theories are popular topics for Kricfalusi, and he has a slew of impressionable young followers, eager to agree and praise him for a chance at winning his approval or gaining entry into the industry.

This, to me, is why people like John Kricfalusi are rather dangerous to this generation's animators and artists. With easy access to the internet and sour grapes-ing from bitter has-beens who have had bad experiences with the industry, young artists are not only discouraged from even trying to get work or make themselves known, they're almost explicitly told that the so-called "Golden Age" of animation is over. All the best have supposedly come and gone, and they left not because animation and the community has been evolving with the times, but because the industry is run by evil, soulless, politically correct automatons that will sooner fire anyone that opposes their way of thinking than let their workers be creative or try new things.

Another point of interest to me is that John K. pointedly avoids talking about abstract or independent works of animation. He typically posts critiques of CGI films, but little else. More rare are the feature films done with stop-motion, rotoscoping, pixelation or otherwise, and when they crop up, he meanders around directly discussing them or even mentioning them for what I can only assume is lack of understanding or anything to say. Persepolis, the film version of the graphic novel by Marjane Satrapi, was released to theaters and the only mention of it by this well-known, widely respected animation guru, was that it was "depressing". When The Fantastic Mr. Fox, directed by Wes Anderson, was approaching release, an entire blog post was dedicated to the movie; that is, an entire blog post was dedicated to a few screenshots of the puppets, followed by a large amount of images meant to mock "furries". This might seem arbitrary to even mention, but I think it's important to discuss what this very influential, supposedly respectable animator does and says in response to things he either doesn't understand or doesn't care about, and what it says about his person and the ideas he gives to his fans.

On the other side of the art world, at the forefront of Japan's stake in post-modernism, is contemporary artist Takashi Murakami. Considered the Andy Warhol of Japan, Murakami is a the founder of a specific post-modern art movement for which he's coined the term, "Superflat". Superflat, in essence, refers to the two dimensionality portrayed in Japanese art, anime, manga and products that reflect the "flatness" and moral emptiness of Japanese consumer culture. It also hints at the dangerous potential of products made purely for consumption (such as the "Hello Kitty" franchise, which existed only in merchandise that referenced no existing media), which allow us to overlook serious insidious intent as long as the product is aesthetically pleasing and cute. Another Superflat artist would be Yoshimoto Nara, drawing flat, two dimensional little girls with somewhat violent or malevolent undertones. Murakami has swept the art world, not only creating worthwhile cultural critique (much like Mr. Warhol), but simultaneously priming the fine art world for illustration, animation, and the "low art" of anime to join the ranks of museum and gallery faire.

Murakami also partners with big commercial names like Louis Vuitton, for whom he sets up show-rooms in the center of all his gallery shows, drawing comparisons to the idea that galleries are much like large salesrooms themselves. His work with pop/R&B artist Kanye West has gotten him a small amount of press, and has opened him up to working with various types of artists and creative minds. Much like many illustrators, he remains open to trying new media and collaboration. His work provides hope for many aspiring young illustrative artists and animators who seek to have their art shown as equal to traditional fine art in museums and galleries, and to be considered true artists in the eyes of the community. It also shows that illustrative art is not entirely superficial as many fine artists or purists would believe, and that it can be meaningful and powerful.

It's worth noting that while the distinction between high and low art is important to some, it isn't to all. Many believe that art is simply that and choose to ignore the notions that different media are more or less valid than others, because in many ways it just perpetuates that notion and ensures the prejudice continues. For many artists, the argument holds no weight at all, and so we must question what's worth discussing or not for the benefit of the community, and for our better understanding of art and how to define it.

The differences in mentality and practice of Takashi Murakami and John Kricfalusi are many, and the impact each has had on the art world and animation industry cover two ends of a spectrum. Murakami takes the common empty imagery of poorly animated Japanese shows (low art) and repurposes it in a manner that cleverly critiques it (high art), and Kricfalusi maintains the mindset that new animation will only ever be a steady decline in morals and quality, using accusatory and bitter claims towards the industry of today. Both site specific issues about the cultures they criticize and seek to define why they are bad and what can be done to "fix" them, in their own ways (more so in the case of Kricfalusi.)

One can wonder if decades from now these artists' insights on pop culture and the animation industry will still be considered relevant, or if their influence will still be felt. On one hand, Kricfalusi is largely influential from his blog, and in that sense he's easily accessible and actually communicates with his fans. Murakami travels and does shows in many countries, spreading his influence around and bringing fresh shows to galleries. Their contributions to the animation world, whether considered bad or good, are still ultimately valuable to the growth of the art and its fans. The filmmakers and their works stand testament to the fact that animation, like any artistic media, is worth getting passionate about.

__________________________________________________________

Animation and Folklore

By Erik Wiedenmann

Looking over all the topics we covered this semester in class, I am struck by the versatility of the animated medium. With films characterized by such vastly different approaches, such as the abstract versus the specific (i.e. propaganda movies), the wide range of possibilities the medium affords become apparent. And yet, when people ask me what kind of work I do, and I respond “animation,” there seems to be a very clear notion of what exactly it is I do: cartoons on computer. I suppose this response should come as no surprise, since my generation grew up at about the same time that computer-generated animation came into popularity. “Toy Story” (1995) and “Finding Nemo” (2003) represent two of the most significant animated feature films of the last two decades. Though hand-drawn animation still hangs on for dear life, it seems to me that computer-generated animation has largely replaced the hand-drawn image as the medium of choice. However, in terms of content, I am convinced that animation will continue to draw on what is arguably its most central pool of inspiration: folk tales. In the following I hope to further expand on the role folk tales play in the history of animation and offer some ideas on why folk tales should figure so strongly in this particular artistic medium.

Conceptual Art from Disney's "Rapunzel" (2010)

This topic has been on my mind for quite some time now. I can’t remember a specific instance in which this theme first came to my attention. I suppose this consideration is no novelty to scholars and critics concerned with animation. And yet, upon further research, I could not find any existing literature that addressed this topic specifically. Perhaps this is simply because the issue is so obvious that none have ventured to explored it in any greater depth. However, as far as I’m concerned, the fact that animation draws on folk tales so frequently should provide some critical insight into the nature and potential of medium itself.

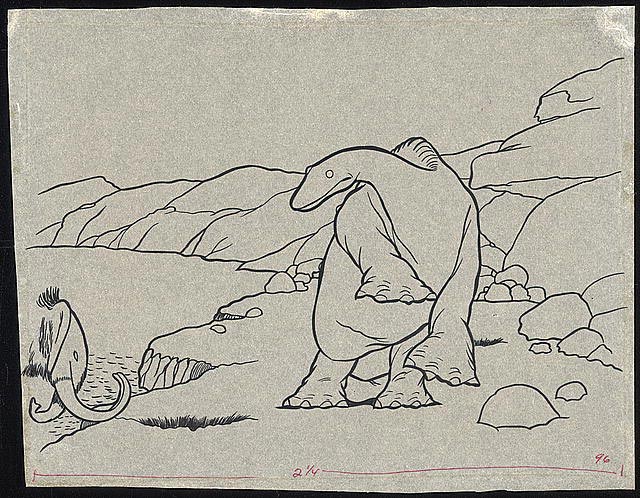

Still from "Gertie the Dinosaur" (1914), Winsor McCay

So when did folk tales first enter the scene? Well, it first took time for artists to become comfortable enough with the medium. In the early beginnings of animation, during the early 20th century, artists such as Emile Cohl and Winsor McKay were interested in experimenting. They wanted to see how much they could accomplish with a frame-by-frame approach. As a result, these early shorts functioned primarily as an exercise of certain technique rather than as a story telling device. As the medium became more sophisticated, the sensation of seeing an image move eventually wore off, so that content began to play a larger role.

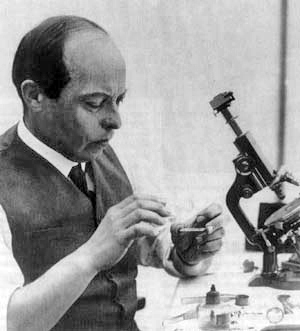

Ladislas Starewich handling some small parts.

Animation soon caught on with a larger audience, as the works of the early pioneers were disseminated. After seeing a Russian performance of Cohl’s “Les allumettes animees” (1908), the director of a natural history museum in Lithuania was inspired to use animation for his next documentary. This man, as the reader may have guessed, was none other than famed stop-motion animator Ladislas Starewich. He had wanted to stage a battle between two beetles, but since the creatures are nocturnal, they would fall asleep every time he turned the camera on. He resorted instead to use dead beetles with attached wire legs. The resulting short film, “Lucanus Cervus” (1910), was the first animated puppet film with a plot and the natal hour of Polish and Russian animation. With the technical skills learned from this first project, Starewich went on to make another short film, this time with a more elaborate narrative. “The Beautiful Leukanida” (1910) was a fable of his own invention, involving two beetles fighting for the love of a beautiful one named Elena. It was this feature, by the way, that had reportedly convinced an English reporter that the insects were, in fact, alive. Starewich continued to employ the same styles and themes in his later short films, including “The Grasshopper and the Ant” (1911), based on a fable by Aesop, and “The Cameraman’s Revenge” (1912) (see below), his perhaps most well-known short. His strong story-telling ability and keen sense of a witty narrative has prompted one contemporary critic to describe him as the “Aesop of the 20th century.”

In Germany, artist Lotte Reiniger was another artist who looked to popular folklore for inspiration. Using exquisite silhouettes shapes she produced some fabulous animations. One of these, titled “The Adventures of Prince Achmed” (1926) (see excerpt below), was based on a combination of tales from the collection 1001 Arabian Nights. The animation is today the oldest surviving feature film. Besides “The Adventures of Prince Achmed,” Reiniger produced a number of other short films based on tales originating from oral tradition, including a dream sequence in Part One of Austrian-American filmmaker Fritz Lang’s “Die Nibelungen” (1924), based on the Medieval German epic, as well as her version of classic fairy tales like “Cinderella” (1954) or "Thumbelina" (1954).

Going down the list of other short films we have seen in class, I can cite a multitude of others that follow that same pattern. However, at the risk of beating a dead horse, I will only bring up a few more, which cannot go unmentioned. Besides a number of short films from the Japanese and Chinese that reference folkloric characters, the Russian animation world can boast about calling Yuri Norstein’s masterpiece, “Hedgehog in the Fog” (1975) their own, and the USA can contribute, among countless others, Tex Avery’s humerous rendition of the classic fairy tale “Little Red Riding Hood,” dubbed “Red Hot Riding Hood” (1943).

The fact that the most recent two Disney features were titled “Rapunzel” (2010) and “Princess and the Frog” (2009) should serve as enough evidence that the trend persists today. We hardly need to go into much detail on that topic. The more pressing issue here is a question I have unanswered until now: Why does folklore feature so prominently in animation?

Obviously, I have no clear answer, though I am willing to offer my hypothesis. To me it seems that the folkloric content is so easily compatible with animation because it offers full freedom to explore concepts that could only be represented with difficulty using live action. With animation, virtually anything can be brought to life, one frame at a time. Starewich would have to rely on some serious CGI if we wanted to animate his bug fights using a computer. Instead, he can move his puppets in any way he chooses, without having to resort to extensive editing to produce a convincing image. Technical matters aside, I believe that animation has always been an instrument of the more common folk. Though, of course, you could argue that not everyone can afford a camera similar to what you might need to make a film, my conviction is that animation holds a markedly different position than film in the cultural sphere. As animation tends to lie further from reality than film, the average viewer is more forgiving. He or she can more easily buy in to an illusionary image or work with more abstract, allegorical themes. This stems from the vocabulary the medium has built up for itself since its beginnings. Therefore, though the medium may transition to more computer-based graphics, I feel confident that the content of animated features will remain true to the simple stories of folkloric tradition.

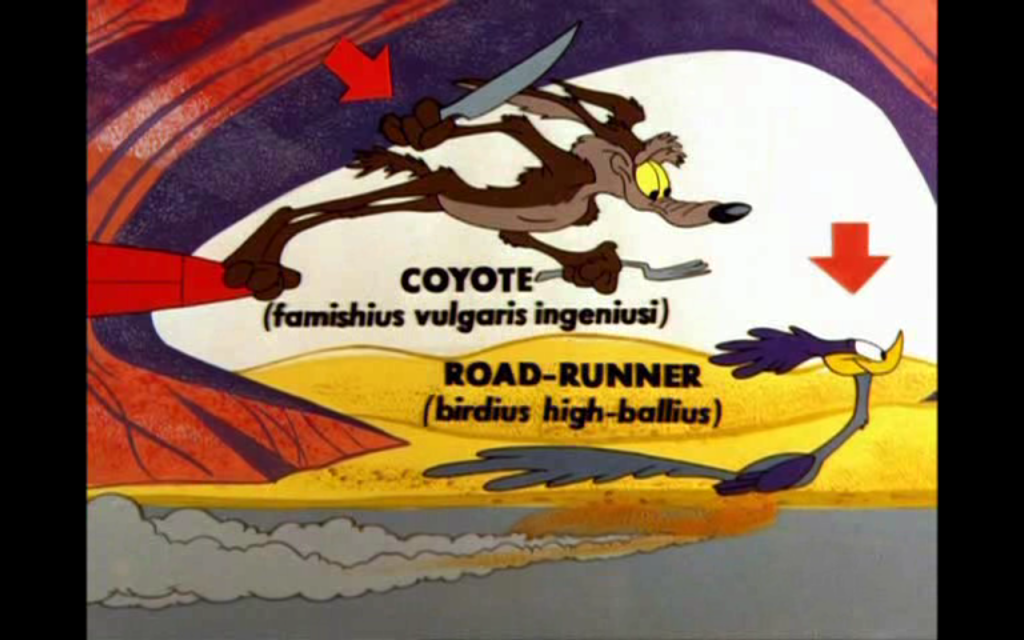

Still from Tex Avery's "Little Hot Riding Hood" (1943)

Of course, there are many more reasons why animation and folklore work so well together. I am thinking about writing a larger paper on this topic somewhere down the road. But hopefully this first bit will act as a some food for thought. Maybe by the time I get around to it, there'll be some more literature on the topic.

Bendazzi, Giannalberto. "Cartoons: One hundred years of cinema animation." Indiana University Press, 1995.'

Palfreyman, Rachel. "Life and Death in the Shadows: Lotte Reiniger's Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Ahmed." Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2011.

Starewicz, W., Shepard, D., Israel, R., Film Preservation Associates., Image Entertainment (Firm), & Milestone Film & Video. (2000). "The cameraman's revenge and other fantastic tales: The amazing puppet animation of Ladislaw Starewicz." Chatsworth, CA: Image Entertainment.

Existential Wiley

by Katrina Miller, for History of Animation

"The Coyote is limited, as Bugs is limited, by his anatomy. To give the Coyote a look of anticipatory delight, I draw everything up—the eyes are up, the ears are up, and even the nose is up. When he is defeated, on the other hand, everything turns down."

-Chuck Jones

The post World War II United States was on the precipice of change- economic, governmental and philosophical. With the onset of the Cold War came subsequent events that insidiously and drastically changed the face of American culture forever, including the Red Scare and the Nuclear Arms race. For the first time in human history, humanity had the power, drive and motive to absolutely destroy itself with a weapon of its own making. Quite literally, the world was teetering on the brink of annihilation, and this knowledge greatly affected art, philosophy, literature and music.

Prior to World War I and II, philosophical movements such as Existentialism and Nihilism were in their infancy, and during the wars, were stored away. Now, in a post-war culture hungry for growth, consumption and an expression/repression of myriad traumas, they exploded in the minds of artists and the public alike. In combination with a paranoid, calculative Cold War psychology, these philosophical movements created dark, austere and anxious movements in the arts. Today, artifacts from this age are looked upon from the safety of a culture comfortable in the knowledge that the Cold War has seemingly concluded. 'Duck and Cover' videos, bomb shelters and the McCarthy Trials can be viewed today through the lens of our security and dissected to reveal their paranoia. However, other paranoid products of the Cold War are far less easily recognizable- specifically, celebrated animation and cartoons.

The brilliant animator behind the iconic Warner Brothers cartoons, Chuck Jones was unquestionably an animator concerned with existential, nihilistic, absurd and Cold War philosophies. Born in 1912, he was witness to both World Wars, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, Korean War and the Gulf War- the latter four being inextricably and undeniably results of nuclear aggression with the former Soviet Union and other communist states. Throughout his life, Jones was surrounded by concepts of an infallible, external foe. He learned of violence taking place elsewhere, related directly to the society he was living in, without actually witnessing it himself. There is no doubt this influenced his animations. His classic 'chase' centric animation (ones involving Bugs Bunny, Elmer Fudd, the Roadrunner or Wile Coyote) definitely seem to reference the current events relative to the nuclear arms race and common philosophical or cultural thought- though it is in his Wile Coyote and Roadrunner animations where Jones' time best manifests itself.

The premise for Jones' Wile Coyote and Roadrunner cartoons is simple: a starving genius Coyote with seemingly unlimited Acme resources tries desperately to catch his speedy Roadrunner prey. Try though he might, however, it always seems as though the Roadrunner is one step ahead of him- ending up the victor by an uncanny streak of luck and ability to manipulate the 'real' into the 'surrreal'. Situations resultant of this explore concepts of perception and reality, animosity and aggression and, of course, mortality. True to cartoon format, fatality is a myth- something to be feared still, but not ever an actual occurrence. In fact, the Coyote faces certain death upwards of three times a short, and is forced to confront his own mortality with a comical sense of impending doom each time. The absurdity of the contraptions the Coyote constructs is counter-balanced by the absurdity of the consequent 'death' he faces as a result.

The Roadrunner is almost certainly an allegorical character. Infallible, nearly omniscent, omnipotent and, yes, very fast, the Roadrunner is, without a doubt, more than just your average absurdist cartoon. His character is never built upon- he never becomes more than just an infallible foe. In fact, the Roadrunner's character breaks even the laws of physics that Jones' himself sets up for the animation- and it is the only character within the animation that does so. The coyote's existence is rooted in the 'reality' of the cartoon. He cannot bend the rules willfully as the roadrunner does- he is bound in the reality Jones' creates. By this path of logic, it is obvious that within Jones' world, there are those who are bound by his 'physics' and those 'exempt' from it. By the reality of the human world, those exempt from the laws of physics are so through an altered perception of reality: hallucinations, dreams and the subconscious. In other words, the only place that people are exempt from physics in the real world is within the human mind. Since Jones is human, we can somewhat safely say his reality must be that of the human world. Thus, the roots for the roadrunner's character lie, at least in part, in the idea that the roadrunner is a manifestation of the subconscious mind.

If the roadrunner does not really 'exist' as an external entity, even in the Jones' created reality, then on whom does his existence hinge? The answer is obvious: the coyote. Without the coyote to fabricate the existence of the uncatchable prey, there would be no roadrunner. The roadrunner represents the imaginary infallible foe so prevalent in nuclear war philosophy and strategy. He is uncatchable, unbeatable, nearly omniscent, and constantly getting the upper hand.

In the context of the roadrunner representing an imaginary infallible foe, what then, does the 'chase' represent? If the roadrunner is the coyote's delusion, then his chase of an uncatchable foe must represent an impossible struggle- a race to see which opponent can outlast the other. Once again, a philosophical relic from the cold war. If two evenly matched foes engage in a struggle, what strategy do they use to try to beat the other? Questions like this are raised a number of times during the Wile Coyote and Roadrunner animations. Will the coyote ever give up? Can his intelligence and determination outmatch the roadrunner's stamina and speed? In one animation, Wile Coyote comes close. In this animation, the roadrunner allows him to catch him because he had been shrunken and posed no actual threat, making the 'capture' more of a tease.

Hypothetically speaking, should the coyote capture the roadrunner, it would be the 'end'. The continued survival of the coyote hinges on the chase. Should he not chase, he would starve. In capturing the roadrunner, he would die. As long as the coyote chases, his life has meaning and purpose. Should the chase end, his existence would be premiseless, a deeply existential concept.

There is an added level of anxiety to the 'end' of the chase- the end to an eternal struggle of two evenly matched sides, especially like during the Cold War, could only be mutual destruction. Should the coyote ever consume the roadrunner, he would also destroy himself by devouring the premise for his existence. Though the roadrunner is just a paranoid delusion, it is the only thing that inspires the coyote to chase. As long as the coyote chases, he is alive. If he should stop chasing, he would starve.

Locked in an endless struggle to survive, both the coyote and the roadrunner serve no other purpose than to exist inside the 'chase'. The roadrunner's existence is dependent on the paranoid delusion of a starving coyote, and the coyote's entire existence would be meaningless without the chase, and, by extension, the roadrunner. In an existential rat race these two foes struggle against a harsh, austere landscape ultimately 'empty' of a real sense of physical geography. Rock formations pierce an endless white sky, while a sense of uncanny unbelievability permeates a fetishized, domesticated “western” landscape. The absurdity and emptiness of the landscape throws into stark relief its place in the harsh philosophical reality of the chase: it is a theatre for war.

And 'war' is really what Wile Coyote and Roadrunner cartoons are about- specifically, the Cold War. As Chuck Jones had been witness to war after war, the build up of aggression and weapons, and a subsequent seemingly endless struggle for dominance, so did his animations reflect the times through which he lived.

Bibliography:

Chomsky, Noam. "Cold War II, by Noam Chomsky." Chomsky.info : The Noam Chomsky Website. ZNet, 27 Aug. 2007. Web. 26 Apr. 2011.

Jones, Chuck. "Chuck Jones Biography." Chuck Jones. Web. 27 Apr. 2011.

Blanc, Mel, Arthur Q. Brian, Tex Avery, Stan Freberg, and Bill Roberts. Looney Tunes Golden Collection: Disc 2. 04 Nov. 2002. Cartoon Collection.

"The Cold War." History Learning Site. Web. 26 Apr. 2011.